Next Up: Hoard’s Dairyman Farm Creamery cheese at the Fort Atkinson Farmer’s Market

People are increasingly interested in where their food comes from. At Hoard’s Dairyman, we practice full transparency from pasture to product.It starts with whole-farm, whole-operation attunement to the land, to the cow, and to the people. We know cheesemakers want milk that will provide a perfect foundation for a top-notch curd. We know consumers want dairy products that fulfill their nutritional needs. We know W.D. Hoard’s vision of a booming agricultural state to be on its way toward realization — Wisconsin being made resourcefully rich by crop rotation, cow rearing, soil nutrition, and conservational productivity. And, finally, we know the importance of embodying these values at every level of our farming, distribution, and publication. You will never have to wonder where your Hoard’s Dairyman Farm Creamery cheese comes from, and you needn’t worry where the rest of your shopping list originates, either. This summer, the Fort Atkinson Farmer’s Market readily joins Hoard’s Dairyman in providing locally derived goods to the community. Beginning May 4 and running through October 26, the market will feature an array of food, musicians, special events, and local artists every Saturday from 8 a.m. to noon. Vendors include SJWHomemade, Beauty and the Bean, Wood Street Bakery, Broadway Bakers, Doug Jenks Honey, and more. Hoard’s Dairyman Farm Creamery will be present each Saturday with every cheese we have available at that time. If you don’t want to wait until the market to taste Guernsey milk cheese at its finest, visit www.hoardscreamery.com to peruse our online shop. Visit the market to shop, socialize, or (respectfully) Midwest-nice people watch. For the ultimate market experience, bring a sun hat and a bouquet-ready tote – and your most trusted cheese aficionado. Join in the crusade for knowing where our food comes from. Shop locally, and support community makers. For more information about the markets, visit https://www.fortfarmersmarket.com/calendar-of-events. We’ll see you there!Down on the Farm: Milking and milk storage

On the Hoard’s Dairyman Farm, we use the finest facilities and the newest technology to bring Guernsey milk from cow to consumer.

Cow in milking robot station.

It’s undeniable: robots are taking over the world as we know it. This is hyperbole, of course. Humans still have control over the future of production (for now). But what does a technological revolution mean for agriculture and for dairying in particular? One way the Hoard’s Dairyman Farm continues to practice the utmost cow care while still providing jobs to workers and milk to distributors is by combining the latest tech with tried-and-true methods. In May of 2019, the first Hoard’s Dairyman Farm cows were milked using four DeLaval voluntary milking systems. This system is considered “voluntary” because it is ready and available for milking whenever a cow chooses to be milked (which, on average, is 2.8 times a day on our farm). Each cow has a tag around her neck that contains information such as her name, number, steps, and milk production. If a cow is eligible to be milked when she approaches the stall, the gate will open, allowing her to enter. A robotic arm then cleans and stimulates the teats, attaches the teat cups, milks the cow, and stores this data in the system and on the cow’s identification tag. This voluntary milking system resides in the newest freestall barn on the farm. Nearby is a traditional milking parlor adjacent to the original freestall barn, where another group of cows is milked. These cows are walked to the parlor twice a day to be milked, and a farm employee uses the same wash, stimulate, and attach method as the robotic, voluntary system. Most of the milking herd are housed in the former barn and are milked using the robots. The remaining cows are milked in the parlor at 4:30 a.m. and 4:30 p.m. daily. Milking parlour

The milk never touches air. The second it’s retrieved, the milk enters a pipeline system that sends it to a stainless-steel tank for storage, where milk must be kept at 38°F. A milk truck arrives daily to collect the milk for delivery to a creamery or distributor. The pipelines and milk tanks are cleaned daily. Sitting at 4.76% fat and 3.52% protein, our milk is not only gathered with care and precision, but it is highly nutritious, too. Next time you bite into Hoard’s Dairyman Creamery Gouda, you’ll know exactly how that milk (and cheese) came to be. If robots pose a threat, it may only be that of proving more useful than we’d care to admit. Voluntary milking aside, what’s not to applaud about making farmers’ jobs easier and dairies more efficient? Maybe the future isn’t so scary — not for the cow, anyway. The “Father of American Dairying”: A brief history of W.D. Hoard and his trailblazing approach to dairy farming.

William Dempster Hoard with a dairy cow

Today, consumers are increasingly concerned with where their food comes from and how it is made. Namely, that it is prepared with thought to sustainable agriculture. W.D. Hoard and, consequently, W.D. Hoard and Sons Co., has embodied this approach from the beginning. In 1885, W.D. Hoard launched Hoard’s Dairyman magazine in wake of his dairy farming column by the same name. Hoard was interested in what made dairying successful and sustainable as a practice. He’d seen the effects of harsh agriculture on the soil that was used to grow crops in his home state of New York, and he believed there to be a better way to steward the land and serve the animals Americans so lovingly depended on. According to W.D. Hoard: A Man for His Time (1985), a Madison newspaper referred to Hoard as “the most distinctly American character since Abraham Lincoln.” A singing school teacher, a water pump salesman, a Civil War Veteran, and a politician, Hoard dabbled in several careers before finding editing and agriculture. Still, his fascination with writing and farming began early, serving as the foundation for the Hoard we celebrate today. Hoard was a mischievous and self-actualizing boy. His mother, herself a lover of language, encouraged him to channel his energy and curiosity into reading extensively and keeping observational journals. As an adolescent, he held an apprenticeship on a farm near his home where he studied “butter and cheesemaking and dairy farming.” It was both during this apprenticeship and through conversations with Chief Thomas Cornelius on the Oneida reservation where his father preached that Hoard learned about conservation and sustainable agriculture. Later, after moving to the Midwest and dabbling in music and sales while caring for his sick wife and their children, Hoard started a small newspaper called the Jefferson County Union, driven by that early love for print. He included in the Union a dairy column that spoke to his “crusade for pure food, especially dairy products.” He advocated for the regular testing of herds and the growing of alfalfa for feed, among other things. It was his opportunity to “preach the gospel according to the cow” in a state where the dairy industry was growing rapidly. Then, in 1885, the first solo Hoard’s Dairyman supplemental publication was printed and included in the Union subscription.“The opening statement of purpose [of Hoard’s Dairyman] went on to project the choiciest and most practical information on management of cows, breeding, butter, and cheesemaking, handling of milk and complete dairy market reports,” wrote Loren Osman in W.D. Hoard: A Man For His Time. Hoard’s Dairyman Farm Guernsey Cows

Despite some initial backlash from longtime farmers who didn’t appreciate Hoard’s suggestion that they needed to make changes to their farming practices, the column found success by staying true to the heart and soul of dairying: the celebration of the cow and her milk. As if being a trailblazing writer and editor wasn’t enough to shape a lasting legacy, Hoard served as governor of Wisconsin from 1888 to 1891. He ran as “the cow candidate,” and had great support from rural communities where people, seeing that he came from similar beginnings as they, knew he would have their interests at heart while in office. Then, in 1899, in an effort to put what he wrote into practice, W.D. Hoard purchased a farm just outside Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin, minutes from the publication office. It is the same farm ¾ and the same office ¾ we own and operate today. There is scarce a person who has worn as many hats as Hoard did, nor who has had a hand in impacting as many fields of study as he. Wisconsin’s landmark dairying and rich, nutritious soil have Hoard to thank for their excellence. His self-made expertise and far-reaching voice made a true and lasting impact on the agricultural narrative of this state and beyond. A man truly for his time, and for our time, too, Hoard and his dairy pioneering live on in the words we put forth in our publications and in the cheese we make from pure Guernsey milk. W.D. Hoard: A Man For His Time quotes Hoard near the end of his time as editor: “None of us dreamed in those first years of seeing Wisconsin as such a great and important dairy state. We only felt that we were dealing with a great and growing principle which, when unfolded to its full working, could bring a new order of agriculture into being . . . I bid you be of good cheer. Keep your eyes to the front. Be forward looking.”The first agricultural publication to have nationwide readership, Hoard’s Dairyman is front and forward to its core. To read or learn more, visit www.hoards.com, and find your own copy of the biography W.D. Hoard: A Man For His Time at https://hoards.com/article-100-wd-hoard-a-man-for-his-time-(wdho).html. Quiz time: How well do you know Guernsey cows?

Once you choose an option, scroll down to see if you had the right answer!

Question 1: Guernsey cows are known for their ____________ hides.

Reddish-brown

Black and white

Mud brown

Albino

What do you think?

Guernsey cows

Answer: 1) Reddish Brown

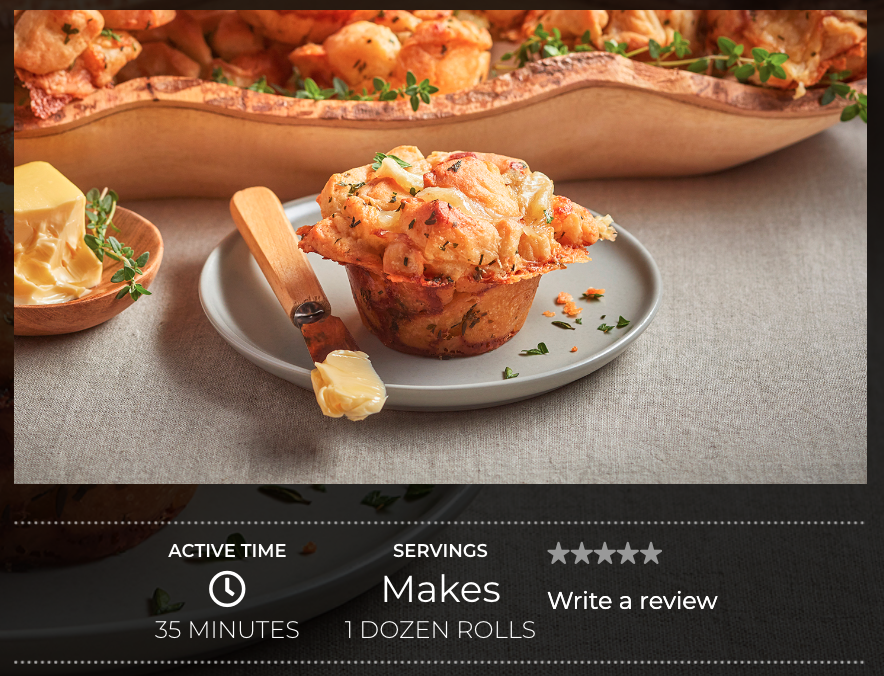

New Recipe: Dinner Rolls with Camembert-Style Cheese

Dinner Rolls made with St. Saviour. This recipe is brought to you by Dairy Farmers of Wisconsin (DFW).

Ingredients: 18 frozen dough dinner rolls1 1/2 wheels (9 ounces) Hoard’s Dairyman Farm Creamery St. Saviour cheese6 tablespoons butter, cubed and melted3 tablespoons minced fresh parsley2 tablespoons snipped fresh chives2 teaspoons minced fresh thyme1 teaspoon garlic powder

InstructionsPlace frozen dinner rolls on a greased 17 x 12-inch baking pan; cover with plastic wrap. Thaw rolls for 1 1/2 hours at room temperature. Cut each roll into six equal pieces. Cover and let rise for 1 1/2 hours.Heat oven to 350°F.Cut St. Saviour into 1/2-inch pieces. Freeze for 15 minutes.Whisk the butter, parsley, chives, thyme and garlic powder in a large bowl. Toss dough in butter mixture.Arrange nine dough pieces and St. Saviour in twelve lightly greased muffin cups.Cover pan with aluminum foil. Bake for 12 minutes. Uncover; bake for 15-18 minutes longer or until golden brown. Let cool for 5 minutes in the pan. Gently run a knife around edges to loosen rolls. Remove from the pan. Garnish with parsley.

Cheesemonger TipSt. Saviour is a soft-ripened, camembert-style cheese with rich, buttery flavor and has a soft, creamy core inside a delectable rind. It’s best served on a charcuterie cheese board at room temperature.Meet Our New Creamery Director

Ricardo Gutierrez

What do you get when you mix a historic dairy farm and an experienced food engineer? Thankfully, we won’t have to wait long to find out. Ricardo Gutierrez joined W.D. Hoard and Sons Co. in 2023 as the Creamery Director and has wasted no time in applying his talents and expertise to our cheese production process. As a practiced cheesemaker who studied in Europe and Mexico before making Wisconsin his home, Ricardo came to us with an abounding background and a salient vision. He is not interested in complacency. He sees beyond what’s before him, what is, to what can be, and is thus equipped to lead Hoard’s Dairyman Farm Creamery cheese to the peak of its potential.“When I was in Mexico and with other companies, I was making cheese the whole week. I enjoy this position at Hoard’s Dairyman because it is cheesemaking, but it is also research and development, sales and shipment – lots of new things. It keeps me busy,” Gutierrez said.During our conversation, I couldn’t help but believe as sincerely as he did in the possibilities embedded within Hoard’s Dairyman as a company and as a leader in cheesemaking. His energy was palpable and infectious. “We’re looking to expand our reach and develop new recipes. We’re hoping to be able to export our cheese to Mexico, too,” he said.Gutierrez was quick to credit the Hoard’s Dairyman Farm Guernsey herd for the quality of our Creamery cheese. The herd’s milk is made up of about 4.8% to 5.2% fat, as opposed to the 3.8% to 4.0% fat of Holstein herds, on average. With quality milk — and quality leadership — comes quality cheese. Gutierrez has only been with Hoard’s Dairyman for the better part of a year, but his leadership transcends date-of-hire. He’s still mid-jump in a boundless surge forward, and he’s bringing all of us at Hoard’s and all of you, our faithful cheese-lovers, with him. Look for more about what Ricardo is bringing to the table in future Creamery Notes issues, and order your own variety of Hoard’s Dairyman Farm Creamery cheese at hoardscreamery.com. Down on the Farm: A Hoard's Dairyman Farm Spotlight

Just like W.D. Hoard himself, we believe that good soil and healthy cows means quality dairy products. That includes the Hoard’s Dairyman Farm Creamery cheese you put on your sandwich, the milk you froth for your coffee, and the yogurt you include in your smoothie. But what does conscientious dairy farming look like? What do milking, cow care, and calf raising actually entail?In an effort to provide our readers with a comprehensive background as to where our milk, cheese, magazine, and brand come from, the Hoard’s Dairy Farm Creamery would like to dedicate the next few issues of its Creamery Notes newsletter to showcasing the Hoard’s Dairyman Farm. Our hope is that, by including one such article in each newsletter, our readers will not only learn more about the dairy industry as a whole and thus adopt a deeper appreciation for their morning cereal and afternoon cappuccino, but, too, that it will lay the foundation for a steadfast honoring of the 139-years-old dairy farming trailblazer that is W.D. Hoard and Sons Co. Over the next few weeks, in the pages of this newsletter, we will share with you the ins and outs of the Hoard’s Dairyman Farm operations, starting next issue with a short biography of the man himself, the “Father of Modern American Dairying,” W.D. Hoard. To brush up on Hoard’s Dairyman content or to order Hoard’s Dairyman Farm Creamery cheese, visit hoards.com and hoardscreamery.com, respectively. This is why you should eat cheese: Cheese lovers, rejoice! Cheese is as nutritious as it is tasty. Read to learn why.

Do you know what makes a cheese platter even better? It’s the ability to indulge in that spread of Gouda, White Cheddar, and Butterkase guilt-free. Cheese contains nutrients such as calcium, magnesium, protein, and vitamins A and B12 that contribute to preventative health benefits. Further, consuming it regularly within serving-size guidelines has been proven to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and increase all-around whole-body health. According to a series of studies published by Advances in Nutrition, a peer-reviewed journal dedicated to scientific and nutritional research, the lowest risk of all-cause mortality among participants was observed at the consumption of approximately 40 grams of cheese per day. This optimal 35 to 40 grams per day held consistent throughout alternative focus groups as well, leveling out steadily (creating an “L” shaped curve) in studies pertaining to the “relative risk of incident” for cardiovascular disease, congenital heart disease, and stroke. This means people who consumed no cheese were at a slightly higher risk for acquiring these diseases than people who consumed 35 to 40 grams of cheese per day. To cheese lovers, this may not seem like much cheese. Forty grams is just a little over 1/3 cup. But it’s important to note that 40 grams is where the data began to level, not rise, meaning there is some wiggle room. Consuming more than this was not directly linked to an increase in relative risk for each of the diseases. Cheese has also been shown to improve cognitive function and bone health and contribute to hip fracture prevention. What’s more, it has the added benefit of pairing well with a variety of foods, making it a healthful alternative to highly processed snacks and meals. Fruits, nuts, bread, and wine are among the most popular pairings, and, should one want to encounter the smell and flavor of a specialty cheese at its finest, eating a chunk of cheese all on its own can be a singularly enjoyable (and nourishing) experience. View our selection of Hoard’s Dairyman Farm Creamery cheeses here.To the cheesery, and beyond! The cheesemaking process is long and involved. Read to learn how your favorite block or curd is made.

Picture this: you’re at a high school graduation party. You plop four — nay, five — tomato and mozzarella skewers onto your plate. You then sing their praises to the host, who points to a cherry tomato plant near the lawn’s edge. Aha! You’re ecstatic to know the source. But wait — where did the cheese come from? At the Hoard’s Dairyman Farm Creamery, we know exactly where our cheese comes from and how it’s made — and so can you.It all starts with high-quality milk from our own Hoard’s Dairyman Farm, and we pride ourselves on having some of the best in the nation. From there, it’s about the cheesemaking process: a tradition as old and practiced as milking itself. Cheese began as an inadvertent discovery (forgotten milk turned accidentally to curd) and is now a beloved food. But where does it come from, and how is it made? For instance, did you know that it takes ten pounds of milk to make one pound of cheese? Or that the scale of a cheese’s sweet or bitter taste depends on how much starter culture is added to the pre-curded milk? Or that coagulation is the process during which milk proteins thicken, and rennet refers to added enzymes that move that process along? Maybe you did – if so, your basic cheese knowledge far surpasses my own. But in case this is new and unfamiliar territory, let’s start from the beginning. According to The Dairy Farmers of Wisconsin, the cheesemaking process begins with the immediate pasteurization of a milk delivery. Pasteurization is the process of heating milk to a specific temperature for a set period of time in order to kill off harmful bacteria that may be found in raw milk. From there, starter culture (friendly bacteria) and rennet are added. Starter culture turns milk sugars (lactose) into lactic acid, and rennet kickstarts coagulation, triggering the beginning of the milk’s transformation. After between 30 minutes to two hours of setting, the milk binds together to form curd. The curd sits in a bath of whey — a liquid made up of water and milk protein — which needs to be drained so that cheesemakers can retrieve the curd. The more whey that is released, the harder the cheese will be. Similarly, the smaller the curd, the harder the cheese will be, and vice versa. Once the curd has been drained and cut, it’s time for salting and cooking. Salt enhances flavor, develops texture, and is a natural preservative. It may be used in various ways throughout the cheesemaking process: added directly into the fresh curd, sprinkled on top of the curd once formed, or used in a brine bath. A cheesemaker may also add herbs or other ingredients while the curd cooks.Once the curd is pressed into a form, the pieces naturally knit together to create a solid shape. The harder the curd is pressed into its form, the firmer the cheese will be. Softer variations such as mozzarella are heated and stretched rather than pressed.Finally, the cheese is either left to ripen in a temperature-controlled room or served fresh.From liquid to solid to table to mouth, the process of cheesemaking is precise and hands-on. Next time you eat a mozzarella ball, you’ll be doing so with the arresting knowledge of how it came to be. Order your own Hoard’s Dairyman Farm Creamery cheeses here. Antarctica’s first and only Guernsey cow

A cow—possibly Klondike—on her way to Antarctica. CBS / GETTY IMAGES

In 1933, American naval officer Richard E. Byrd returned to the Antarctic base Little America — constructed on his previous (and first) voyage to the continent — in the interest of mapping and claiming land around the South Pole. An all-around explorer, Byrd was accustomed to spending chunks of time with expedition crews. This time, however, he had three unique companions: Deerfoot Maid, Foremost Southern Girl, and Klondike Gay Nira — Guernsey cows from Massachusetts, New York, and North Carolina. According to The Mariners’ Museum and Park, Byrd secured these cows’ attendance by partnering with the American Guernsey Cattle Club. The trip would promote dairy, he said, as well as the individual dairy farms the cows came from. Indeed, the cows made headlines across the nation, their leader’s thirst for adventure igniting an illustrious spark even The Great Depression couldn’t extinguish. Klondike was pregnant upon boarding the southern-bound ship — intentionally. Byrd’s hope was that she would give birth within the Antarctic circle. Alas, the calf, Iceberg, was born just north of it. Still, Iceberg quickly became an American hero, spawning books and comics and ads telling the tale of his singular journey.During the latter part of the trip, Klondike acquired frostbite and had to be put down. Additionally, young Iceberg returned home with rickets and a severe Vitamin D deficiency. This is not terribly surprising, since cows are typically comfortable at temperatures 20 degrees F and above, but it raises questions as to whether the Guernseys should have been brought to Antarctica in the first place, and if Byrd would have been permitted to bring them there today. Regardless, the expedition lives on in Antarctic and dairy lore alike. How many cows can say they’ve traveled beyond their pasture or barn? Iceberg went where no cow has gone before. And where no cow probably ever will again. Source: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Richard-E-Byrd/Byrds-accomplishments